The story of my life. Where to start? At the beginning, I suppose...

I was born at Tsarskoe Selo on November 3 (according to the old calendar, November 15 on the new calendar), 1895, the first child of Tsar Nicholas II and Tsaritsa Alexandra of Russia. I was a large baby, weighing ten pounds, and with what my great-grandmother and Godmother Queen Victoria of Great Britain called an "immense head." It must have been truly huge, as I had to be birthed with forceps. My poor, dear Mama - that was certainly not the last time I would cause her difficulty! But I digress. On that day, Papa wrote in his diary:

"A day I will remember for ever...At exactly nine o'clock a baby's cry was heard and we all breathed a sigh of relief! With a prayer we named the daughter sent to us by God 'Olga'!""The name of Olga we chose as it has already been several times in our family and is an ancient Russian name," my father wrote to my great-grandmother Victoria. "Olga" is Russian for "Holy," chosen in part to honor my father's youngest sister and another of my Godmothers, my dear aunt Olga Alexandrovna, with whom my name day would be celebrated each year on July 11 (July 24 on the new calendar). My life as an Orthodox Christian began not two weeks after my birth, with my Christening as "Olga Nikolaievna" on November 14;

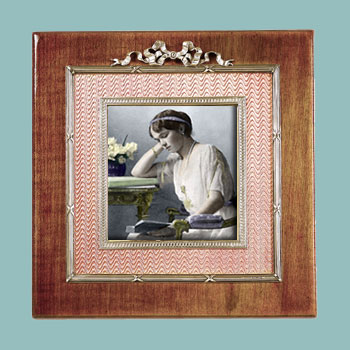

"The christening in the Big (or Catherine) Palace church was a splendid function. The baby was taken to church in a gold coach like a fairy Princess. A mantle of cloth of gold covered her little body, and she was carried in state by old Princess Galitzin on a golden cushion. The Dowager-Empress and Queen Olga of Greece were her godmothers, and it was the Empress Marie, wonderfully young-looking for the grandmother's role, who held the baby during the ceremony. The Grand Duchess Olga was a fair, fat baby, not showing as a tiny child the good looks that were to be hers when she grew up."

~ Sophie Buxhoeveden

In our household, I was known simply as "Olga Nikolaievna" - addressed by my first name and patronymic, as all my siblings were. I was often called Olya and Olishka by family members.

My family doted on me from the beginning - especially my father, to whom I would grow extremely close as I got older. "In the morning I admired our delightful little daughter," he wrote in his November 6 journal entry, "she does not look at all newborn, because she is such a big baby with a full head of hair." My hair was said to have been long and black back then, which is rather odd considering that I grew up to be almost blonde!

Papa sometimes bathed me, Mama nursed me, and both parents thoroughly enjoyed watching me develop. Mama in particular - she never let me out of her sight during my first weeks of life! She had me sleep near her in her rooms, and insisted that I accompany her and Papa on a state visit to France when the time came. When my first nanny arrived in mid-December of 1895, my parents were dreadfully disjointed by my removal to the nursery. Of the matter, my father wrote: "Dear Alix was in a state, because the arrival of the new English nanny will entail some changes in our family life; our daughter will have to be moved upstairs, which is a pity and rather a bore!" Mama would check in on me quite often, however - for which she would be criticized by the nanny, whom I can only assume wanted to be left alone to do her job. For the first two years of my sheltered life, my closest friends were relatives. I would play with my cousin Irina, who was about the same age as I. I would also romp with my cousins Maria Pavlovna the Younger and Dmitri Pavlovich, who were the wards of my Aunt Ella. But my dearest friend of all entered my life in June of 1897 - that friend being my sister, Tatiana Nikolaievna. Our parents chose Tanya's name so that we could be like the sisters Olga and Tatiana Larina in Pushkin's Eugene Onegin. We would only be separated by illness for the entirety of our lives, sharing a room, even, in the Children's Apartments at the Alexander Palace (and everywhere else we went). Our father wrote in fall of 1897:

"Our little daughters are growing, and turning into delightful happy little girls...Olga talks the same in Russian and in English and adores her little sister...The Cossacks, soldiers and Negroes are Olga's greatest friends, and she greets them as she goes down the corridor."

Tanya and I could have been rivals, being so close in age, but for some reason, that never, ever became an issue between us. Tanya was always considered the great beauty, while I was the great charmer (I can talk a good line, anyway!). Pierre Gilliard, the man who would become our dear French tutor, wrote of us:

"Through her good looks and her art of self-assertion, [Tatiana] put her sister Olga in the shade in public, as the latter, thoughtless about herself, seemed to take a back seat. Yet the two sisters were passionately devoted to eachother. There was only eighteen months between them, and that in itself was a bond of union."According to Mother's friend Lili Dehn, I became beautiful in my own right as I grew older:

"[Olga] was a most amiable girl, and people loved her from the moment they set eyes on her. As a child she was plain, at fifteen she was beautiful. She was slightly above middle height, with a fresh complexion, deep blue eyes, quantities of light chestnut hair, and pretty hands and feet. She took life seriously, and she was a clever girl with a sweet disposition."At any rate, I think the "sweet disposition" the greater compliment, as I fear I was sometimes rather bossy towards my sisters and servants. And as for taking life seriously...well, let's just say that when unfortunate or exceedingly inane things happened, I couldn't help but be upset by them. While I enjoyed socializing very much, I did not like the complication of being a grand duchess out in society. I was happy to let Tanya - who was practical and very good at dealing with the trials and tribulations of being a royal - handle the pomp and circumstance, while I remained the romantic dreamer.

"One sensed in her a 'good Russian young lady' who loved solitude, reading poetry, who was impractical and disliked everyday matters," wrote Sydney Gibbes, our English tutor, of my nature.

In 1899, 1901, and 1904 respectively, my siblings Maria Nikolaievna, Anastasia Nikolaievna, and Alexei Nicolaievich were born. My sisters and I became "OTMA," and Tatiana and I the "Big Pair" to Mashka and Nastya's "Little Pair." Tanya and I would sometimes exclude our younger sisters in the early years, but our love and admiration for them overcame any real conflict we might have had.

Tanya and I were almost always dressed identically (usually by the dressmaker Lamanova of Moscow, Tania the clotheshorse reminds me). Usually, Mashka and Ana would be dressed to coordinate with us. All four sisters wore Coty perfumes. I liked Rose Thé the best...though to be honest, I've never been as interested in clothes or toiletries as Tatiana is. Mama and OTMA each patronized a Russian military regiment, mine being the 3rd Hussar Yelizavetgradsky. I petitioned that my troops might wear white fur-lined cloaks with their dress uniforms, which spurred them to add the following to their regimental song:

We Hussars are not of foil,

We are all of damask steel.

How we value Olga's name,

Our white cloaks and our flag of fame!We all had pets, mine being a pretty tabby cat named Vaska. For the most part, the animals got along almost as well as we did (Tanya might try to deny this, but...her dog snores!).

The four of us were best friends and partners in crime in a number of prankish endeavors. I greatly enjoyed a good joke, and loved to have a good time with my family. Here is a particular favorite from 1915, of which I wrote to my father with perfectly straight face:

"...I am sitting in Mr. Gilliard's rooms near the door of his water-closet where Trina's little nasty girl Katia is sitting locked in by Anastasia and myself. We've just drawn her along the dark passage and pushed her in. The weather became very cold and it was snowing today and the snow didn't melt. We had a lot of fun when we went for a drive with Isa but Mother was receiving visitors all the time which was rather dull. Mordvinov had breakfast with us and told us a lot of interesting things but we interrupted him every moment as usually and didn't let him go on. It's always a great pleasure for us to read Alexei's letters. He writes such nice and funny letters without Pyotr Vasilyevich's help...Katia is still locked in the W.C. She is knocking and wailing behind the door but we are implacable..."

We were allowed to be children for longer than many would have expected, but it didn't bother us. I was happy to be free from the harshness of reality...or at least, as free as I could be.

Mama's great friend, Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden, wrote of me:

"[Olga] was very straightforward, sometimes too outspoken, but always sincere. She had great charm, and could be the merriest of the merry. When she was a schoolgirl, her unfortunate teachers had every possible practical joke played on them by her. When she grew up, she was always ready for any amusement."The head of the secretariat at the Ministry of the Imperial Court, A. A. Mosolov, wrote of my girlishness:

"Olga was at seventeen already quite a young lady, but she still behaved like a girl. She had beautiful light hair, her face - a wide oval - was purely Russian, not particularly regular, but her remarkably delicate coloring and her pretty smile, which disclosed remarkably even, white teeth, gave her a great freshness...Olga's character was even, good, with an almost angelic kindness."Life with my family was idyllic, except perhaps for the lack of suitable friends outside of our family circle. Aside from my sisters, my best friend was probably Margarita "Rita" Khritova, one of Mama's ladies-in-waiting. Mama, being an extremely religious Orthodox Christian, sheltered us from the ills of the world from the beginning. She believed that most of the Russian girls of suitable age and social standing would be bad influences on us. So, she chose to hold us close to her, instilling in us the desire to lead spiritually-fulfilling lives.

"To keep the children quiet," Mama wrote to Papa in 1902, "I made them think of things and then guess them. Olga always thinks of the sun, clouds, sky, rain or something belonging to the heavens, explaining to me that it makes her so happy to think of that."

But like most children - except perhaps for my angelic sestra Mashka - I would have my less-than-perfect moments.

"She was hot-tempered but did not bear grudges," wrote our English tutor, Dr. Gibbes, of me. "She had her father's heart, but lacked his consistency."

"Olga Nikolaievna was hot tempered" Sophie Buxhoeveden wrote of me, "and would sometimes turn suddenly cross when she was offended."

This I can't deny! I was stubborn, sometimes rough in my manners, and occasionally yelled to get my points across. Our poor, saintly mother often reminded me to calm my volatile temper: "Mama kisses her girly tenderly and prays that God may help her to be ALWAYS a good loving Christian child. Show kindness to all, be gentle and loving, then all will love you."

Mama would ask me to set a good example for my younger sisters: "You know so well to be sweet and gentle with me, be so towards sisters too." She would also remind me that as the oldest sister, I was becoming a young lady, and needed to comport myself accordingly: "You are growing very big - don't be so wild and kick about and show your legs, it is not pretty."

Anna Vyrubova, another close friend of Mama's, attributed my sometimes-trying moodiness to cleverness and straightforward thought and action:

"Olga was perhaps the cleverest of them all, her mind being so quick to grasp ideas, so absorbent of knowledge that she learned almost without application or close study. Her chief characteristics, I should say, were a strong will and a singularly straightforward habit of thought and action. Admirable qualities in a woman, these same characteristics are often trying in childhood, and Olga as a little girl sometimes showed herself willful and even disobedient. She had a hot temper which, however, she early learned to keep under control, and had she been allowed to live her natural life she would, I believe, have become a woman of influence and distinction."By age eight, I had discovered the joys of reading and my aptitude for learning. At the age of ten, I met my friend and French tutor Pierre Gilliard, also lovingly known to us as 'Zhillik.' Monsieur Gilliard, though initially struck by our lack of educational advancement, came to appreciate my unique intelligence and love of learning:

"The eldest, Olga Nikolaievna, possessed a remarkably quick brain She had good reasoning powers as well as initiative, a very independent manner, and a gift for swift and entertaining repartee. She gave me a certain amount of trouble at first, but our early skirmishes were soon succeeded by relations of frank cordiality. She picked up everything extremely quickly, and always managed to give an original turn to what she learned. I well remember how, in one of our first grammar lessons, when I was explaining the formation of the verbs and the use of the auxiliaries, she suddenly interrupted me with: 'I see, monsieur. The auxiliaries are the servants of the verbs It's only poor "avoir" which has to shift for itself.'"As it turns out, Zhillie isn't completely right about me picking everything up - I have a terrible memory for thick histories filled with dates. Ugh - midieval history! Nevertheless, he and my other tutors - Dr. Gibbes, Pyotr Vasilyevich Petrov, &c. - were quite fond of me, and I of them. I often signed letters to Petrov - known playfully as P.V.P. - as "Number One Pupil, Olga."

Zhillik, like Sophie Buxhoeveden and Ana Vyrubova, also appreciated my frankness and discernment:

"Olga, the eldest of the Grand-Duchesses, was...very fair, and with sparkling, mischievous eyes and a slightly Retroussé nose [I call it my 'humble snub']. She examined me with a look which seemed from the first moment to be searching for the weak point in my armour, but there was something so pure and frank about the child that one liked her straight off."From the beginning, our mother took an interest in our learning. When Zhillik first came to us, she watched him carefully as he conducted our French lessons. She took a very personal interest in our language fluency (even though we were not always as advanced as some thought we should be), and liked to help us choose books as we became better readers. We spoke Russian, English, French, and some German. In 1912, she wrote to her friend and former governess, Madgie Jackson,

"If you know of any interesting historical books for girls, could you tell me, as I read to them and they have begun reading English for themselves. They read a great deal of French and the 2 youngest acted out of the Bourg. [Bourgeois] Gentilhomme and really so well, make Victoria tell you all about it. Four languages is a lot, but they need them absolutely, and this summer we had Germans and Swedes, and I made all 4 lunch and dine, as it is good practice for them."

Outside the schoolroom, I would read voraciously - especially as I grew older. While I would slog through the boring stuff to get it out of the way, I REALLY liked novels. Often, Mama would find me reading books missing from her boudoir. "You must wait, Mama," I would tell her playfully, "until I find out whether this book is a proper one for you to read." I kept my journals faithfully, wrote poetry, and enjoyed exchanging ideas with others. Gleb, the son of our Court Physician, Dr. Botkin, would give me his poems to critique, which I liked very much. I would also converse with Dr. Botkin himself, whom I considered a "deep well of profound ideas," and addressed in my letters as "Dear Well."

My sisters and I were also interested in a number of athletic and artistic pursuits. We would hike, play tennis, and ride bicycles when the weather was clement. I was considered quite a good equestrienne. "The three of us went riding in the afternoon for the second time," I wrote Papa in the spring of 1915. "Maria rode your Guardemarine and I rode Regent."

Tanya was a proficient pianist, and Nastya and Mashka were accomplished painters. I never considered myself much of a songbird, but I was very heartened when Baroness Buxhoeveden wrote this of my musical talents:

"[She] was the cleverest of the sisters, and was very musical, having, her teachers said, an 'absolutely correct ear.' She could play by ear anything she had heard, and could transpose complicated pieces of music, play the most difficult accompaniments at sight, and her touch on the piano was delightful. She sang prettily in a mezzo-soprano. She was lazy at practicing, but when the spirit moved her she would play by the hour."I was also considered quite graceful, and an accomplished dancer. I loved dancing, though my sisters and I didn't have the chance to attend a great many society balls. We would dance at our Aunt Olga's house in St. Petersburg on many weekends, and there were occasional informal "balls" with friends and officers at home, on the Standart, and at Livadia. The first real, official ball I attended, however, was that held in celebration of my sixteenth birthday in 1911, at New Livadia Palace. Anna V. wrote of the event:

"Flushed and fair in her first long gown, something pink and filmy and of course very smart, Olga was as excited over her debut as any other young girl. Her hair, blonde and abundant, was worn for the first time coiled up young-lady fashion, and she bore herself as the central figure of the festivities with a modesty and a dignity which greatly pleased her parents. We danced in the great state dining room on the first floor, the glass doors to the courtyard thrown open, the music of the unseen orchestra floating in from the rose garden like a breath of its own wondrous fragrance. It was a perfect night, clear and warm, and the gowns and jewels of the women and the brilliant uniforms of the men made a striking spectacle under the blaze of the electric lights."I did not attend many after that (well, there were a few the following winter), and did not make my Debut into St. Petersburg society in 1914 as my parents had planned I would. Sophie Buxhoeveden wrote,

"The two elder girls were to have made their official appearance in St. Petersburg society in 1914, when the Empress had meant to resume the giving of Court balls in their honour. They were always present at the rare functions given at Court after 1915."The Great War changed many plans our family had made. The innocent, carefree Olga of earlier years gradually drifted away as Russia became more and more unstable. As the oldest child in the family, I was keenly aware of the terrible state of the world, and it depressed me terribly. It pained me especially to find that the press and others were seeking to slander and destroy my parents and their friends. They didn't know the truth, or didn't care. And it made me furious! Towards the end, Papa and I would take long walks and spend hours in his study, trying to find out why such things were happening to us. The war, my father's abdication, and our confinement made us even closer than before. I loved my father very much, and so wanted to make things better for him and for Mama. I became even more religious than ever, finding strength in Christ and his teachings. I wore my cross around my neck, as is customary for Russian Orthodox Christians, and a likeness of St. Nicholas - Papa's patron saint - on my chest. Being a girl of tremendous fire, it was difficult me to accept God's will, but I did, and was made a Martyr for it by the Russian Orthodox Churches.

According to Gleb, I

"was by nature a thinker and as it later seemed to me, understood the general situation better than any member of her family, including even her parents. At least I had the impression that she had little illusions in regard to what the future held in store for them, and in consequence was often sad and worried. But there was a sweetness about her which prevented her from affecting anybody in a depressing manner, even when she herself felt depressed."I was eager to do my part to help my father and my country through something positive, though at times it was very difficult for me to deal with reality. Tanya, Mama, and I went to work as Red Cross nurses, helping to treat the war-wounded. At first our mother was a bit wary of allowing Tanya and I to do this, but we insisted, and undertook a nursing course of some depth. Mashka and Nastya were not allowed to nurse, so they contributed in other ways. They sponsored the hospital at Feodorovsky Gorodock, the village at Tsarskoe Selo, visiting the wounded when they could.

Lili Dehn wrote of OTMA's contributions:

"All the sisters were utterly devoid of pride, and, when they nursed the wounded during the war, they were known as the Sisters Romanova, and thus answered to the numbers 1, 2, 3 and 4".It was a trying experience for me - I had little patience for cruelty and waste, and no stomach for the suffering of others. I would rather roll bandages and comfort the recovering. Tatiana and Mama were quite good at focusing on the tasks at hand in surgery, but ultimately, I could not handle it. I suffered a nervous breakdown, and was forced to stop nursing.

My desire to do good, however, could not be quelled. From the time I received my first monthly allotment of pin-money, I was always interested in spending it wisely. While we wore lovely clothes and lived in beautiful palaces, our mother tried to teach us the value of money and industry as we grew up. Each month, we were given the then-equivalent of only two pounds sterling in spending money. Out of this, we were expected to cover the costs of our note-paper, perfumes, and any gifts we might want to give family members or friends. I would spend much of it on gifts and charity.

My sisters and I were made honorary chairwomen of various philanthropic committees as we reached our teens, and I always took my duties as fundraiser seriously.

"She was generous," Baroness Buxhoeveden wrote of me,

"When Olga Nikolaievna, at the age of twenty began to have some of her money in her own hands, the first thing she did was to ask her mother to allow her to pay for a crippled child to be treated in a sanatoria. On her drives she had often seen this child hobbling about on crutches, and had heard that the parents were poor and could not afford a long and costly treatment. She had at once begun to put aside her small monthly allowance to go towards paying for the treatment."We would also help our mother in her various fundraising projects. When in the Crimea, for example, we would spend "White Flower Day" selling baskets of white flowers for the benefit of tuberculosis patients in local hospitals. This beautiful custom, however, ended in 1914, after which we would not return to Livadia.

For all the sadness, chaos, and terror the War brought, there was one small consolation - the pressure to marry was greatly lessened. From the time we were born, my family intended for OTMA and Alexei to make suitable marriages. Mama once wrote of our marriage prospects:

"...with anguish I think of their future - so unknown! Well, all must be placed into God's hands with trust and faith. Life is a riddle, the future hidden behind a curtain, and when I look at our big Olga, my heart fills with emotion and wondering as to what is in store for her - what will her lot be?"My parents wanted me to be happy, so they never forced anyone onto me, but I know they worried about us. "The Empress thought a loveless marriage impossible," Sophie Buxhoeveden once said, "and was quite ready for her daughters to wait till the right men came to claim them." My mother in particular seemed to be oddly ambivalent about our marriage prospects. On one hand, I'm sure she feared losing us to situations in which she could not insure our happiness. Yet on the other, she knew we couldn't live as her children forever.

Unfortunately for me, most suitable royal matches dwelled outside of Russia, and away from my parents and siblings. In June of 1914, just two months before the War, our family made a state visit to Romania. The unspoken understanding was that I was to meet Prince Carol in hopes that perhaps we might want to marry. I, however, would not have it. "I am a Russian and I mean to remain a Russian!" I told Zhillie as we made our way to Romania.

Unfortunately, the marriage game didn't end there. There was talk - and a great many inside jokes within our household - of my marrying Prince David of Great Britain. Some hoped I would marry my friend and cousin Mitya, though the faintest glimmer of possibility there was ended with his involvement in Father Grigori's murder. My aunt Meichen desperately wanted to marry me off to her son Boris, but even my parents thought it too cruel a scheme to even consider. He was much too old for me. And he was...rather disgusting. I hate to be cruel, but there it is.

As for my own marriage choices, it makes little sense to speak of them now. I have felt passionately in my short life. I have wanted marriage and children. But sadly, these were not my "lot."

I wouldn't want to end this little narrative on such a sour note, so I'll close with some hopeful words from my father, which I paraphrased in a letter written while in captivity in Tobolsk...

"Father asks to...remember that the evil which is now in the world will become yet more powerful, and that it is not evil which conquers evil, but only love... "God be with you,

Olga